Humanity’s Choice

By Nicole Clark

It was a cold morning in mid August in 2013 when the choice finally

dawned on me, after almost 3 years at University and two ecology majors,

not once before had this thought crossed my mind. Not once in the

times I analysed data, climate data, plant data and all species data-

had I once visited the ideal that this choice was something all of

humanity had to face. When the thought settled into my mind, I was grief

struck, I was awe struck, I felt sick, tangled and distraught. Not

once had something hit so far home. In all the textbooks, in all of the

lectures, in all of the labs ; not once had something hit me as hard as

this did- in all of my time whilst doing Environmental Science had I

ever even imagined. What happened on that cold morning in mid August

2013 in my lecture? I understood something that I never did before. For

you to understand the concept in just the right amount of intensity

that I felt at that very moment, you need to let go of the pre-conceived

notions that fill you with ideas about the environment. Think about

what those words ‘threatened’ and ‘endangered’ mean to both you, and to

others around you.

When I ask- what does the label endangered or threatened species

really mean? The first thing you think is, ‘Oh my god, extinction!’ Your

first response will probably be ‘my children will never get to see

rhinos and elephants- they will only be in text books’. We all know

about the risk of losing species, and we all know about the attempts to

save those species at risk and we all know that no attempts to

save species will ultimately lead to their extinction. But, have we

ever even considered what will happen if we can’t ‘save’ them all? In

mid August 2013, something dawned on me.

Blinded by ideals, my class mates and I worked on the lesson task and

discussed species loss. We had been given a task to devise ways to

save species at risk and how they can be saved using modern

Environmental Science. With a blind heart full of dreams, my initial

thought was ‘all species would be saved- because surely all

environmentalists will save them all’. By the end of the class, my

thinking suddenly changed. Then it dawned on me, there are over 30,000

endangered/threatened species (Baillie et al, 2004), we simply cannot

save them all, no amount of conservation will save them all. My heart

sunk and it was then that I knew.

I was faced with the cruel raw reality standing before me. Humanity

has to make a choice, in fact humanity has NO choice but to make a

choice. Humanity must decide who stays or goes, my hands were shaking

and I looked over at my class mates with their hearts still full of

dreams and it felt like my heart stopped.

So… now I ask the question, how do we make that choice, how do we

make the most difficult and the most important decision a single species

(humanity) is ever going to make? Similarly, a scarier thought… what

if… we had, already made that choice? What if in all the haste to save

the rhino, the panda and the Siberian tiger, have we unconsciously made

the wrong choice? On that cold mid August morning I was faced with the

biggest reality of them all, what will humanity choose?

To understand the complexity of this seemingly endless swell, we need

to explore the ideas behind species loss, and what it really means to

‘lose’, a species. What is the context of these words ‘threatened and

endangered’, what do they mean? How is each label determined? Baillie et

al, (2004) states, these words are used as a reference point from the

IUCN list (International Union for Conservation of Nature) and are

categorised according to risk intensity. Different risks for each

different species can lead to the loss of an entire species OR simply

extinction. To assess this risk intensity, scientists look at the number

of, the increase/decrease of a population of a species over time and

the relative breeding success of the given species over time. From these

deductions the risk for each species is ranked into categories,

serving as a reference point as to just how intense the risk of losing

the species in question is.

The real question here is, can humans make the most important choice

of all, can we chose to save the right species from the brink of

extinction? Can we really make the right choice and can this choice be

unaided by previous influence? Is it something we can do with a

subjective eye? Of course we can- right? Well actually, probably not.

It isn’t something we like to think about too often, least of all

scientists… but, humans are bias. But just how bias are we?

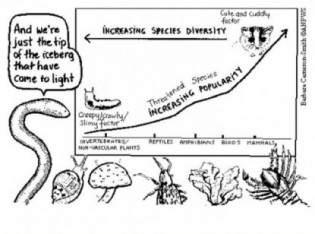

Scientists now know that humans have what is called a ‘cute’ meter in

our brains, it’s called ‘Baby Schema’ (Glocker et al, 2009), this

means, we respond to things we deem as cute, and from the age of 3 our

brain is programmed to respond to specific features that mimic a human

infant . The human brain responds to features such as, a rounded bulbous

head, high cheekbones and large wide bulbous eyes (Sanefuji et al

2007). So… in actual fact, since humans find these traits more

appealing, where ever these traits are evident, humans have an automatic

emotional response to cuddle, nurture and care for any species with

similar aesthetics. Therefore, in saying this, it isn’t too surprising

that the most documented and heard of threatened species management

cases worldwide belong to the cute, the cuddly and the downright

adorable (Smith, 2007). That is, most threatened species management goes

to species such as (to name a few), the panda, tiger and rhino.

Unfortunately, it is all too true, and those species which are not

deemed as ‘cute’, actually do receive less attention, in fact it’s well

documented that this is the case. Scientists even have a name for it,

it’s called; the Noahs Ark problem (Perry, 2010).

Aside from the lack of subjectivity and clear bias, the fact is, we

(the human species) are selecting cute animals to save. By simply

selecting our ‘favourite species’, it is unlikely to affect the planet

in droves isn’t it? No. Actually, it is likely that in making this

choice to save only ‘cute species’, other species will die as a result

(Chaplin et al, 2000). It pains me to say this so casually and without

emotion, yes- other species will die. If we painfully ignore that

concept as part of our future- on the other hand, what if choosing to

let a species die could actually not just wipe out one or two species

(which is sadly a given and therefore not the most devastating aspect

here) – but instead an entire community and the community that

depends on that community? Not only will humanity have to consciously

decide which species will go extinct, humanity could unconsciously

choose to let the wrong species go extinct! All, without even

considering the consequence, that humanity too will suffer! Such a

species like this in science is what is known as a keystone species, and

if you lose a keystone species, entire communities can cease to exist

(Dobson et al, 2006).

So what are keystone species? What do they do? What happens if you

remove a key stone species? Keystone species are those species that

mandate the function and unity of ecosystems. Keystone species hold all

species in the community together in what is known as a trophic level

order (Duanne et al, 2002). Any species loss is biodiversity loss and

when a keystone species is lost, it is likely to cause a cascade

effect, or a trophic cascade. As a result, entire communities hang in

the balance. Ecosystems provide services to humans in what is

collectively referred to as, ecosystem services (Chaplin et al, 2000).

If a keystone species is lost, not only will an entire community

collapse, humans will lose the service an ecosystem has to offer too.

For example, removing a keystone species such as tuna, can affect an

entire food web causing mass species extinction and mass economic

welfare to the fishing industry (Chaplin et al, 2000).

Humanity has created an experiment. Not only could we make the wrong

choices, but there’s nothing to say we haven’t already! There’s nothing

to say, that ANY of the species we are trying to save are OR

are not keystone species, just like the tuna. Consider this, it’s a

scary terrifying thought to question whether saving a species such as

the panda or rhino is right, but quite another to consider the

possibility that a tiny little invertebrate such an ugly snail or warty

toad, holds the key to the survival of every living species within the

community the rhino or panda exist in. Then ask yourself, what happens

if we a) never know of their existence and b) never know AND let them go

extinct in our quest for cuteness? Sadly, the answer is, we don’t know.

Scientists don’t know what the consequence of selecting cuteness will

bring, we don’t know what the consequence of our already pre-programmed

appeal to nurture and care for animals (that remind us of our own cute

little infants)-will bring.

Humanity must decide, not only do we have to roll up our sleeves and

open our minds to the incredibly difficult decision as to what species

we will save, we also we need to be aware that our decision is

pre-programmed instinct. An instinct designed to assist us in rearing

our own young, which can be incredibly emotionally driven and without

subjectivity (Sanefuji et al, 2007). All the while, these choices are

strongly affected by the biological desire to protect all that we deem

as cute. If all of the animals we want to save are all ‘cute’, which

cute ones do we save (will it be the rhino, the elephant, the tiger or

maybe the panda?) Nevertheless, perhaps more importantly, we also need

to consider- in our quest to save cute, have the not- so -cute

completely lucked out? Are we creating our own unique biodiversity loss,

is there a not –so- cute keystone species being driven to extinction?

If so, what will happen to the environment if we make the wrong choice?

OR have we already made the wrong choice?

Humanity has a choice, this is no ordinary choice, it is a choice

that hangs in the balance of our very existence. Asking the question to

anyone, ‘which species should live and which species should die’, is

truly shocking, but there is nothing more real about this statement. On

that cold day in mind August 2013, it wasn’t the fact that some species

were not going to be saved that shook me. No, it was the likely hood

that humanity would make the wrong choice and would not save the right

ones. For me, it’s not simply the question of asking which ‘species we

save and which we should not’, for the question in its self is riddled

with discomfort. It’s also not even the notion of which ‘not- so- cute’

keystone species we should save or let go- despite that it’s even more

confronting and uncomfortable as the later. No, for me, it’s considering

the likely hood that anything that isn’t cute- be it keystone species

or not, will be forgotten and will not be saved ; going down in history

as humanity’s secret pushed- to- the –corner, shame. The shameful

choice, the choice that alters the future of the planet for every single

living thing. And, perhaps the most confronting of them all on that

cold mid August morning- the thing that terrified me the most and the

thing that really hit home? That subconscious scientific affirmation

that, I, as an Environmental Scientist -already knew the answer. The

answer, that humanity has probably already made that choice. Because

for humanity, the final decision will always be the elephant in the room

(or not, depending on how ‘cute’ that elephant is) and when faced with a

double-edged sword for who stays and who goes; for humanity, not unlike

all species, instinct will always reign supreme.

Baillie, J., Hilton-Taylor, C., & Stuart, S. N. (Eds.). (2004). 2004 IUCN red list of threatened species: a global species assessment. IUCN.

Chapin III, F. S., Zavaleta, E. S., Eviner, V. T., Naylor, R. L.,

Vitousek, P. M., Reynolds, H. L., … & Díaz, S. (2000). Consequences

of changing biodiversity.Nature, 405(6783), 234-242.

Dobson, A., Lodge, D., Alder, J., Cumming, G. S., Keymer, J.,

McGlade, J., … & Xenopoulos, M. A. (2006). Habitat loss, trophic

collapse, and the decline of ecosystem services. Ecology, 87(8), 1915-1924.

Dunne, J. A., Williams, R. J., & Martinez, N. D. (2002). Network

structure and biodiversity loss in food webs: robustness increases with

connectance. Ecology letters, 5(4), 558-567.

Glocker, M. L., Langleben, D. D., Ruparel, K., Loughead, J. W., Gur,

R. C., & Sachser, N. (2009). Baby schema in infant faces induces

cuteness perception and motivation for caretaking in adults. Ethology, 115(3), 257-263.

Perry, N. (2010). The ecological importance of species and the Noah’s Ark problem. Ecological Economics, 69(3), 478-485.

Sanefuji, W., Ohgami, H., & Hashiya, K. (2007). Development of

preference for baby faces across species in humans (Homo sapiens). Journal of Ethology,25(3), 249-254.

Smith, K. Funding Distribution of the Endangered Species Act. (2007)

No comments:

Post a Comment